The Fear Project Part IV: The Tiny Kingdom of the Kitchen Table

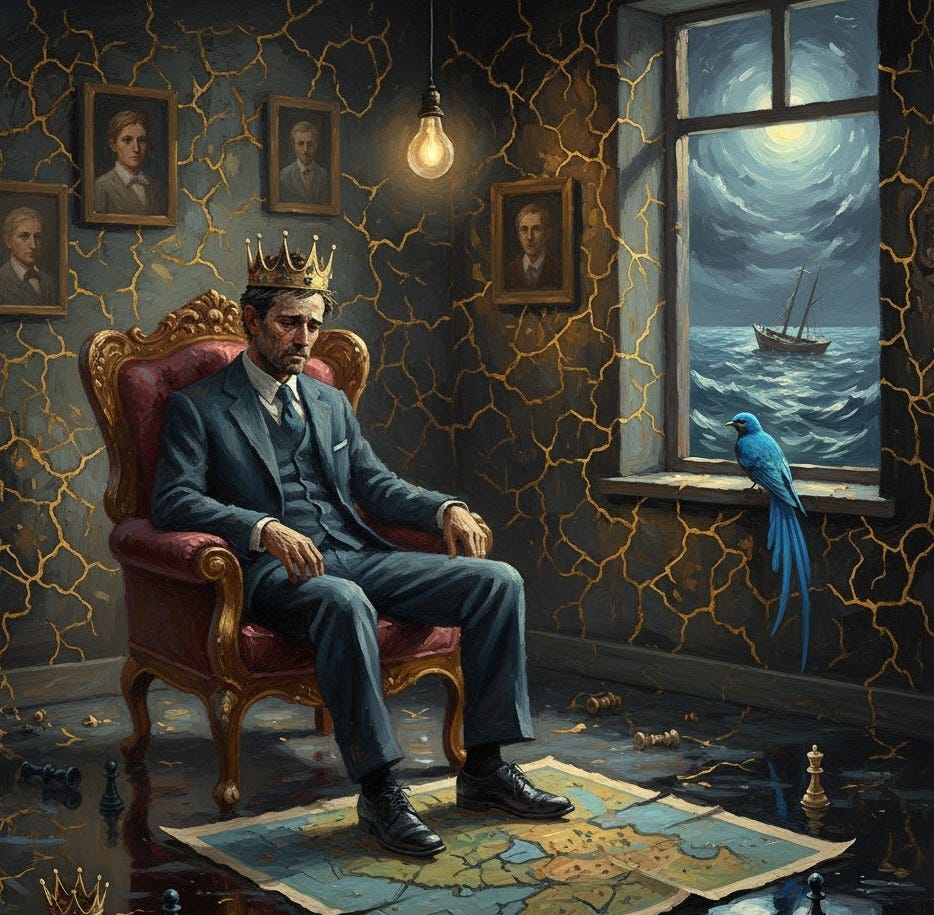

There is a map of a very small country that is never drawn but is nonetheless fiercely governed, its borders defended with a quiet, desperate vigilance. This country is the space between two people in a committed love, an invisible territory with a population of two, whose entire Gross Domestic Product is measured in intimacy and trust. In some of these unions, one partner assumes the role not of a co-inhabitant, but of a nervous sovereign, a monarch ruling from a throne of anxiety. The kingdom they preside over is not a vast and bountiful land, but a cramped and precarious one, perpetually besieged by imagined threats. Every decision, from the choice of a vacation destination to the tone of a morning greeting, becomes an act of statecraft, a measure to secure the borders and quell potential insurrection.

The partner is not a fellow citizen but the most proximate and unpredictable foreign power, whose independent thoughts are clandestine operations and whose personal growth is a looming secession. This monarch, ruling from the kitchen table or the shared bed, is motivated not by malice, but by a profound and corrosive terror: the fear that if they ever loosen their grip, even for a moment, the entire kingdom will collapse into anarchy and ruin. This is the realm built on the fear of failure and the desperate need for control, a dominion where security is sought through subjugation, and where the most significant cost is the very love the sovereign is trying to protect. The tragedy is not that the kingdom is small, but that its ruler believes it can only be maintained through a state of perpetual, low-grade warfare, turning the one person they vowed to cherish into the primary subject of their surveillance and the principal object of their fear.

This governance of intimacy is rooted in a deep and often unacknowledged psychological constitution, a mind that has learned to equate surrender with annihilation. The controlling partner is an architect of preemptive strikes, their strategies dictated by cognitive biases that frame the relationship not as a collaboration but as a zero-sum game. At the core of this is a profound fear of losing control, which manifests as a compulsive need to manage every variable, from the household budget to the partner’s social calendar.

This is the work of a mind suffering from a kind of relational vertigo, where the slightest deviation from the expected plan feels like a plunge into the abyss. They operate under the cognitive distortion of catastrophic thinking, where a partner’s forgotten promise to take out the trash is not a minor oversight but the first tremor of an earthquake that will surely level the foundations of their life together. To prevent this imagined collapse, they employ manipulation not as a tool of overt cruelty, but as a necessary instrument of policy. It can be as subtle as a guilt-inducing sigh or as complex as a long-con campaign to isolate their partner from friends who might “give them ideas.”

Their refusal to compromise is not born of stubbornness but of a genuine, visceral belief that their way is the only bulwark against chaos. To cede a point is to surrender a strategic outpost, to allow a breach in the fortress wall. Beneath this iron will lies not strength, but a brittle terror of consequence. This fear animates the lies, the careful omissions, the rewriting of history to cover a mistake. Admitting fault is an act of treason against their own regime; it suggests a fallibility that the sovereign cannot afford to display, lest the citizenry—the partner—begin to question their absolute authority.

This internal landscape is often a result of an insecure attachment style formed in the crucible of early life, where love was conditional and safety was contingent on performance. Consequently, the fear of failure in love becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. To foreclose the possibility of being abandoned or found wanting, they engage in acts of unconscious self-sabotage. They will provoke an argument just when things are peaceful, a preemptive strike to prove that disaster is always lurking.

They test their partner’s loyalty with escalating demands and manufactured crises, not to be difficult, but to reassure themselves that the kingdom’s defenses will hold against the ultimate siege. It is a desperate audit of love’s inventory, a constant search for proof that they will not be overthrown. This leads to the most exhausting of labors: the performance of not being enough. This fear generates a frantic energy, a need to over-perform in their career, as a parent, as a lover, all to justify their position and shore up their perceived value.

They are constantly proving their right to rule, terrified that if they stop for a breath, their partner will finally see the insecure, frightened person behind the crown and stage a coup. This defensive posture creates a feedback loop of anxiety; the more they control, the more their partner pulls away, and the more their partner pulls away, the more they feel the terrifying confirmation that their grip is, and has always been, the only thing holding it all together. They become prisoners in a jail of their own making, pacing the battlements of a fortress that keeps love out just as effectively as it keeps their fear in.

This intimate autocracy does not emerge in a vacuum; it is subtly underwritten and validated by the larger social and historical currents that shape our understanding of love, power, and security. For generations, the architecture of marriage was explicitly hierarchical, a socio-economic contract that often granted the husband the legal and cultural authority of a monarch. While those formal structures have largely dissolved, their ghosts linger in our collective consciousness, whispering that control is a natural, even necessary, component of a stable partnership.

The modern economic landscape, with its relentless emphasis on individual achievement, competition, and quantifiable success, has transposed the logic of the marketplace onto the sacred ground of the relationship. Love is now often viewed through the lens of investment and return, risk and security. A partner becomes an asset to be managed, their growth a potential liability if it deviates from a shared, predetermined business plan. The cultural narrative of the “power couple” further reinforces this, celebrating a union not for its tenderness or resilience, but for its consolidated strength and social capital. Failure, in this context, is not just emotional heartbreak but a form of social and economic bankruptcy. This pressure creates a fertile ground for the fear of not being enough to flourish, as individuals feel compelled to constantly perform their worthiness, lest their “stock” should fall in the eyes of their partner and the world.

Furthermore, the digital age has armed the anxious sovereign with unprecedented tools of surveillance. The shared calendar, the location-tracking app, the open social media profile—these are the modern instruments of state security, allowing for a level of oversight that past generations could never have imagined. A partner’s “like” on a photograph can be interpreted as an act of foreign espionage, a new friend a potential fifth columnist. This technological ecosystem normalizes a degree of transparency that can easily bleed into intrusive control, blurring the line between healthy connection and anxious monitoring.

The fear of change, too, finds an ally in a culture that fetishizes stability and nostalgia. We are sold an image of love as a static, unchanging idyll, a safe harbor from the tumultuous world. When a partner wishes to change careers, go back to school, or simply evolve as a person, it can feel like a violation of this implicit contract. The controlling partner’s resistance is not just personal anxiety; it is a reflection of a society that often punishes risk and sanctifies the predictable. They become the enforcers of a cultural status quo, sabotaging their partner’s growth not just for their own comfort, but because they have internalized the message that change is a threat to the institution of the relationship itself. The kingdom’s borders must be maintained, not only because the sovereign is afraid, but because the world outside has taught them that secure nations do not change their maps.

The governance of a relationship through fear and control exacts a hidden but exorbitant tax on the emotional and spiritual resources of both individuals. This is the quiet, uncalculated cost of maintaining the illusion of power. For the sovereign, the expenditure of energy is immense. The mental bandwidth consumed by monitoring, planning, and worrying—the constant vigilance required to manage their partner’s life is a massive drain on their own potential. This is time and intellectual capital that could have been invested in their own career, their own friendships, their own self-development. They are the chief financial officer of a failing state, pouring all the treasury’s resources into the military and secret police while the nation’s infrastructure, joy, creativity, and spontaneity crumble into disrepair. This is the “Control Tax,” an invisible levy on every interaction, making every conversation a negotiation and every shared moment a potential security risk. For the one being controlled, the cost is even steeper.

It is the opportunity cost of a life half-lived, of dreams deferred or abandoned to maintain the peace. Every time they swallow their own opinion, cancel a plan with a friend, or decline a professional opportunity to appease the sovereign’s anxiety, a small piece of their own sovereignty is ceded. Over time, this amounts to a slow and devastating erosion of the self, a form of psychological gerrymandering where their own territory of identity shrinks to a non-threatening size.

The entire relational economy stagnates. When one partner’s fear of change becomes official policy, the couple is denied the dividends of growth. The new job that could have brought financial stability and personal fulfillment is rejected. The move to a new city that could have brought new experiences is vetoed. The difficult conversation that could have led to deeper intimacy is avoided. The relationship’s portfolio, once diversified and full of potential, becomes a single, low-yield bond held in the name of security. Furthermore, a significant cost is accrued in the form of emotional debt. The lies told to avoid consequences, the mistakes covered up, the authentic feelings suppressed, each one is a small loan taken out against future trust. This debt doesn’t remain static; it compounds with the silent interest of resentment.

Eventually, the balance becomes too large to ignore, and the relationship faces an emotional bankruptcy from which it may never recover. The illusion of security purchased by the sovereign is, in fact, the most reckless of gambles, a high-interest loan taken out against the very asset it purports to protect. The kingdom may look peaceful from the outside, its borders secure and its daily routines orderly, but it is hollowed out from within, running on a deficit of authenticity and financed by the slow depletion of two human souls.

There comes a point in the life of such a tightly controlled kingdom when the pressure becomes unsustainable. The reckoning arrives not always as a sudden, violent revolution, but often as a slow, inexorable collapse. It can be precipitated by an external crisis, a job loss, a serious illness, the death of a parent, an event so large and uncontrollable that it shatters the sovereign’s illusion of omnipotence. Suddenly, their meticulously crafted internal policies are irrelevant in the face of an invading force they cannot manipulate or command. In this moment of genuine powerlessness, their entire identity as the competent, all-knowing ruler is thrown into question, and the fear they have so long suppressed floods the throne room. More commonly, however, the breakdown is an internal affair. The controlled partner, after years of ceding territory, finally reaches their own border of self-respect. Their compliance has not brought the promised peace, only a stifling emptiness. The rebellion may take the form of an affair, an emotional betrayal that serves as a desperate declaration of independence. Or it may be a quieter, more resolute departure, a packing of bags in the dead of night, leaving the monarch to survey a suddenly empty and meaningless kingdom.

The consequence is a profound and painful dissolution. The sovereign is left to confront the very failure they dedicated their entire reign to avoiding. Their strategies of control, designed to prevent abandonment, have become the direct cause of it. They are deposed, not by an external enemy, but by the predictable and righteous uprising of a human spirit that cannot indefinitely tolerate being governed. For the partner who leaves, there is the difficult work of reclaiming their own nationhood, of rediscovering the topography of their own desires, ambitions, and voice after years of living as an occupied territory. The failure of accountability in the aftermath is often the greatest tragedy. The deposed monarch, still trapped in their defensive psychology, may frame the collapse as a betrayal, a testament to the partner’s untrustworthiness, further validating their lifelong belief that control was always necessary. “You see?” they declare to a court of none, “The moment I let my guard down, they fled.” Genuine reform is impossible without a complete dismantling of this internal narrative.

The reckoning is not complete until the sovereign can look upon the ruins of their relationship and understand that they were not protecting a kingdom, but holding a hostage. The ultimate consequence is a terrifying loneliness, the silence that falls when the subject of one’s control is finally gone, revealing that the throne was, all along, just a chair in an empty room.

To dismantle such a regime of fear and step into the uncertain democracy of a true partnership requires an act of profound courage—a willingness to abdicate the throne. The solution begins not with new rules of engagement, but with a new constitution, one that replaces the principle of control with the principle of trust.

The first and most critical step for the fearful partner is to turn their formidable intelligence inward, to begin the work of understanding the origins of their terror. This often requires the guidance of a therapist, an outside mediator who can help them trace their fear of failure and chaos back to its source, be it in the unresolved traumas of childhood or the anxieties of adult life. It is the work of learning to self-soothe, to manage the internal vertigo without needing to clutch onto their partner for balance. They must learn to sit with the discomfort of uncertainty, to understand that the absence of control is not the presence of catastrophe, but the presence of possibility. This is a shift from being a monarch to being an explorer, willing to navigate the unpredictable landscape of a shared life without a predetermined map.

For the relationship itself, pragmatic solutions can build the scaffolding for this new way of being. Couples can schedule regular, non-confrontational “state of the union” meetings, creating a safe and structured forum to discuss fears, aspirations, and grievances without either party feeling ambushed. In these conversations, the goal is not to win a debate or secure a concession, but to practice the art of deep listening, to hear the fear beneath the anger, the longing beneath the criticism.

Adopting principles of non-violent communication, where feelings are expressed as personal truths (“I feel scared when plans change unexpectedly”) rather than accusations (“You’re always so unreliable”), can de-escalate the sense of conflict and transform the dynamic from a battle for control into a collaborative effort to make both partners feel secure. The call to action is to redefine what it means for a relationship to be “successful.” It is not a state of perfect, unchanging harmony, but a dynamic and resilient system capable of rupture and repair. Success is not the absence of failure, but the grace with which two people navigate it together. It is the willingness to apologize, the courage to be vulnerable, and the faith to believe that letting go of your partner’s hand does not mean they will walk away, but that they will, by their own free will, choose to walk beside you, not as a subject, but as a sovereign of their own, in a lasting and powerful alliance of equals.

Click Here and enjoy the Deep Dive on this article on YouTube